September 2 marks an important date in Vietnam — the day the country’s independence was proclaimed in 1945. It is an occasion for the Vietnamese people and national authorities to celebrate a symbolic moment in modern history, as well as to honor the national hero, Ho Chi Minh.

In this article, we look back at the events that led to this Proclamation of Independence. We will first discuss the context in which it took place — the end of the Second World War — and then examine how Ho Chi Minh and his allies seized this moment to strengthen their presence and gain legitimacy.

However, the Proclamation of Independence on September 2, 1945 did not put an end to France’s ambitions in the region. It would take several more years and two wars before the Socialist Republic of Vietnam could be proclaimed across the entire Vietnamese territory.

Feel free to contact us to organize your tour in Vietnam.

The Declaration of independence of september 2, 1945 in the context of World War II

The context in which Vietnam’s Declaration of Independence was born was that of the Second World War, during which the Allies fought against the Axis powers (notably Germany, Italy, and Japan).

Indochina remained on the sidelines of the Pacific War between the Americans and the Japanese until July 1944, when the U.S. Air Force began bombing Japanese posts in Indochina from southern China and the Philippines. In January 1945, two raids by Task Force 38 devastated not only the Japanese merchant fleet but also Vietnamese supply junks and part of the French fleet (the cruiser Lamotte-Picquet was bombed and sunk). By the end of 1944, the Japanese forces decided to end the status quo with Vichy France and to free the region from French control. After French Admiral Decoux refused to place his forces under the authority of the Emperor of Japan, Operation Meigo Sakusen was launched: during the night of March 9, 1945, a large number of French officials were captured, and French and Indochinese troops were attacked.

After this offensive, the French colonial administration was effectively destroyed. The Japanese declared the independence of the three Indochinese states while keeping control over the political leaders they placed in power. Bao Dai, previously “King of Annam,” became Emperor of Vietnam and formed a government with authority over the entire Vietnamese territory (the French concessions of Tourane-Danang, Haiphong, and Hanoi were reintegrated into the Empire, as well as Cochinchina, despite Cambodian claims to this southern region).

This independence, however, was not the one celebrated today. From the very beginning, the communist independence movement denounced this government as a “puppet regime” serving Japanese interests.

The government set up in April 1945 lasted only a few months, unable to handle the severe economic and humanitarian crisis that swept the country from early 1945. Since 1941, the French colonial government in Indochina — under the Vichy regime — and the Japanese had requisitioned most of the agricultural and mineral production to meet Japan’s demands. Rice, maize, coal, and rubber were all sent to Japan. Shortages of food supplies, combined with soaring inflation, led to the famine of January 1945, which caused over one million deaths. Powerless in the face of this crisis and before Japan’s capitulation, the government resigned in early August 1945.

At that moment, most of the forces present rallied behind the Viet Minh, thus legitimizing its declaration of the country’s independence and the creation of the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

It is now essential to discuss how the Viet Minh, led by Ho Chi Minh, skillfully seized the opportunity presented by the end of World War II to emerge as the country’s legitimate liberating force.

The Declaration of independence and the Viet Minh’s rise to power

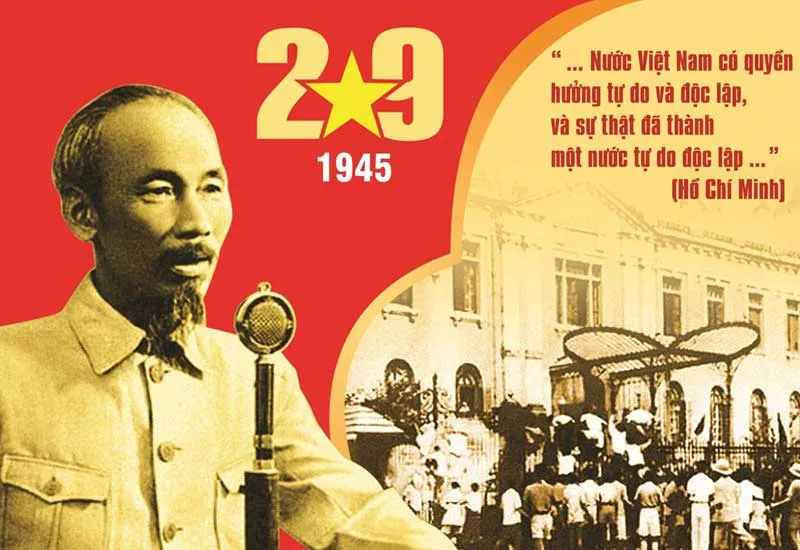

The Declaration of Independence on September 2, 1945 symbolized both liberation from foreign domination and the triumph of a political movement — the Viet Minh — and its charismatic leader, Ho Chi Minh.

Ho Chi Minh, whose real name was Nguyen Ai Quoc, had left Moscow in 1938 and stayed in China until 1941, in the Red bases of Guangxi. He was behind the 8th Congress of the Central Committee of the Indochinese Communist Party (founded in 1930) held in May 1941. The Committee then agreed on a new political line: the primary goal of the struggle should be national independence, by uniting all Vietnamese under the broadest possible front. Social revolution and class struggle were to take a back seat. The Viet Minh (“League for the Independence of Vietnam”) was thus founded, bringing together both communist and non-communist nationalists to achieve Vietnam’s independence.

From its inception, the Viet Minh worked to create National Salvation Committees (Hoi Cuu Quoc) — organizations aimed at mobilizing the population. Militias were also formed under the command of strategists Vo Nguyen Giap and Chu Van Tan.

Ho Chi Minh and his fellow fighters (General Giap on the right)

Despite the imprisonment of many activists, this grassroots work allowed the Viet Minh to gradually expand its influence. The Japanese coup of March 9, 1945 was perceived by Ho Chi Minh as a major opportunity. He requested help from the Americans in the fight against Japan — and succeeded: weapons and training were provided to the Viet Minh by the U.S. military.

A National Convention was convened on May 19, 1945, in Tan Trao (about 70 km from Hanoi), with Viet Minh delegations from across the country participating. The convention placed national independence on its agenda and appointed Ho Chi Minh as head of the National Salvation Committee. In August 1945, with American support and the cooperation of the Indochinese Guard — and without opposition from the Japanese garrison — the Viet Minh took power in Hanoi (August 19) and then in the imperial capital, Hue (August 22).

Ho Chi Minh and his American allies in 1945

By this time, the Viet Minh was in a position of strength across the country and capable of negotiating with the Allies. On September 2, 1945, Ho Chi Minh fulfilled the Convention’s project by declaring the country’s independence and proclaiming the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

The symbolism of the new political regime

The event of September 2, 1945 marked the country’s independence, the rise of a legitimate political force (the Viet Minh), and the establishment of a new political regime — the Democratic Republic of Vietnam.

In his speech at Ba Dinh Square, before a massive crowd, Ho Chi Minh — making his first national appearance — referred to the U.S. Declaration of Independence (1776) and the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and of the Citizen (1791), both of which, he said, had been betrayed by the colonialists. The event also revealed the enduring symbols of the new regime:the red flag with a yellow star, emblem of the Viet Minh, later becoming the national flag;the motto “Doc Lap – Tu Do – Hanh Phuc” (Independence, Freedom, Happiness) and a national anthem.

The event carried strong philosophical, symbolic, and strategic significance: by taking control before the arrival of Allied disarmament missions, the Viet Minh positioned itself advantageously to negotiate and decide Vietnam’s future.

Photos of Ho Chi Minh during the Declaration of Independence

Unfortunately, other actors — especially the French authorities — would not allow the Viet Minh to carry out its project.

A short-lived independence: The failure of the fontainebleau agreements and the beginning of war

While the Declaration of Independence marked the Viet Minh’s victory over other liberation forces and consolidated its popular base, foreign powers soon challenged its authority.

In Cochinchina, as early as September 1945, the reconquest of Indochina began with British support. In Tonkin, the presence of the Yunnan army — allied with the Viet Minh — became problematic for Ho Chi Minh, who signed an agreement on March 6, 1946 with French commissioner Jean Sainteny, negotiating the withdrawal of Chinese troops. To extend this agreement, a delegation from the Democratic Republic of Vietnam went to Fontainebleau, and Ho Chi Minh was received in France on July 14, 1946 as a head of state.

Jean Sainteny and Ho Chi Minh in 1946

Despite the apparent international recognition suggested by this reception, the French negotiated to ensure that the word “independence” would not appear in the agreements and that French troops could remain stationed in Vietnam for five years. Implementation of the March 6, 1946 agreements proved impossible. Soon, violent incidents multiplied: the Battle of Haiphong (November 1946) and the Battle of Hanoi (December 1946). The latter truly marked the beginning of war between the Viet Minh — now fully controlled by the communists — and the French forces.

The fighting lasted eight years, engulfing the entire Indochinese peninsula and spreading into neighboring Cambodia and Laos.

The Vietnamese Declaration of Independence of September 2, 1945 was a highly symbolic act, but it was only a step toward full independence and reunification. The Democratic Republic of Vietnam (North Vietnam) was recognized as independent in 1954, following the Geneva Accords, and the Socialist Republic of Vietnam was established only in 1975, after the withdrawal of American troops.

For further reading, we recommend the following works:

Pierre Brocheux, Histoire du Vietnam contemporain, la nation résiliente, Fayard, 2011, 280p

Céline Marangé, Le communisme vietnamien (1919 – 1991) : construction d’un Etat-Nation entre Moscou et Pékin, Presses de Sciences Po, 2012, 611 pages

Jacques Dalloz, La guerre d’Indochine, 1945-1954, Seuil (Points Histoire), 1987, 320 pages

Ivan Cadeau, La guerre d’Indochine : De l’Indochine française aux adieux à Saigon. 1940-1956, Editions Tallandier, 2015, 667 pages